Am I crazy?

Am I insane?

It’s a question people can have after they have an experience—or experiences—that defy easy explanation.

Skepticism is valued in our society. Being skeptical shows you’re no fool. Knee-jerk skepticism, even cynicism, is easy.

Sometimes it takes work and courage to ask questions.

You may not like the answer either. The truth may show you to be somewhat deficient, mistaken. That’s a blow to the ego. It’s much more comfortable to walk the line of what’s generally accepted about how the world.

If you’re a scientist, the truth or saying the wrong thing can get your career stalled, sidelined, or even ended.

Am I crazy?

You may not want to ask this publicly, but you still want to know.

You want to trust your perceptions.

The researcher

When she was compiling her research, she kept hearing one odd story after another from the people she interviewed.

One girl spoke of her dead brother visiting her bedside in the hospital.

Another elderly man spoke of how his deceased mother patted his hands and comforted him as he faced his terminal diagnosis.

She encountered one story after another like these. On and on. These types of visions were far more common than she had been led to believe before she started her research.

Are these dying people hallucinating? Is there some universal tendency toward wishful thinking? If so, why are there so many things in common about their experiences?

The dying patients believed they had encountered their dead relatives. This belief had effected a change in their outlook. It had made them, to a person, feel optimistic about dying.

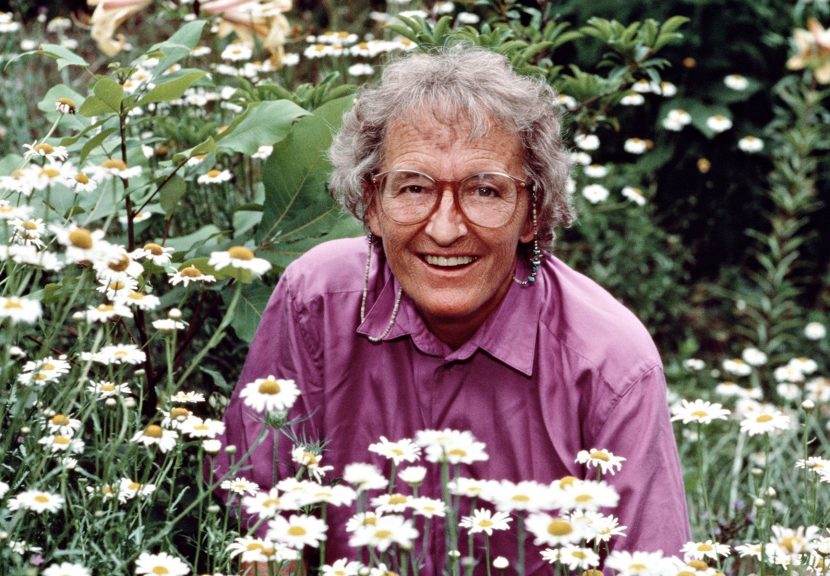

The researcher was Elisabeth Kübler-Ross and she was working on her seminal book On Death and Dying: What the Dying Have to Teach Doctors, Nurses, Clergy, and Their Own Families. She was studying the process people underwent when they died. The topic was somewhat taboo in the early 1960s. She had encountered so many of these stories that it seemed natural to write a chapter on the topic.

“What do you think?” she asked her friend and assistant. A chaplain had been assigned to her by the hospital to help her with her research. They had become confidants.

“It’s a good chapter, and it’s interesting, but if you want to get this book published, you better leave it out,” the Rev. Mwalimu Imara said.

She heeded his counsel.

On Death and Dying was groundbreaking in every sense of the word. It popularized the concept of there being five stages of grief: denial; anger; bargaining; depression, and acceptance. That became a major theoretical framework. Every student of psychology, medicine, and nursing has to learn about the stages today.

Without Rev. Imara’s sage counsel we might not have heard of those stages and we probably wouldn’t know her name today.

Later in her career, when Kübler-Ross went on to study these deathbed visitations in greater detail and various ways to contact the dead, her professional reputation suffered something of a decline.

She and her husband had founded a center for the dying and their families that they dubbed Shanti Nilaya, which meant “Home of Peace” in Sanskrit. The institution was one of the first modern hospices. Kübler-Ross was against euthanasia because she believed that it prevented dying people from coming to terms with their life.

The researcher was studying out-of-body experiences, mediumship, and spiritualism. She had become professionally involved with a conman who had claimed he could channel spirits and summon ethereal entities. He encouraged the members of his church to participate in sex with the spirits and, reportedly, hired several women to play the parts of female spirits.

One participant in the sex sessions reportedly asked, “How is it that an entity, a pure spirit, has cigarette breath?”

Importance of skepticism

Kübler-Ross’s story provides an important lesson for anyone who values critical thinking or is open-minded about the truth: Never Lose Your Skepticism.

You need to have a balanced approach. Never be too credulous. Never be too skeptical. Either extreme will affect your ability to get to the truth.

When you’re analyzing your dreams, follow where your reasoning takes you. To not do so is cowardly. Look for objective and subjective proof and know the difference between the two. It’s important to not be seduced by ideas themselves.

She wasn’t wrong for studying what she studied. She was wrong for losing her objectivity and publicly insisted she didn’t.

In a 1979 interview with People Magazine, she said of the conman, “He has so much integrity. He does not need to be defended.”

There are truths people don’t feel comfortable facing.

People throw the word “crazy” around all of the time. They also say “nutty,” “loco,” “batty,” and “wild.”

When they say those words with a smile in their voice, it’s a compliment. It’s fun to be considered crazy when you’re the life of the party and making everyone laugh. That’s a good kind of crazy.

Channel your inner Steve Martin. Say it: “I’m a wild and crazy guy!” Wear that arrow-going-through-your-head headpiece and shake your head side to side.

When there’s a hint of accusation in a voice calling you crazy, there’s nothing fun about it. Those can be fighting words.

You might feel like your life is coming unhinged. You might have heard voices. You might have seen things that aren’t there. You had a dream that’s so vivid with content so strange you can barely manage to think about it. You might feel challenged to live out the change it’s calling from you.

Then someone says you’re crazy for one reason or another. It’s like a blow to the solar plexus!

When it comes to dreams that are incredibly whacked out, it’s natural to hate how the thoughts make you feel. The inclination can be to try to forget them rather than write them down in your dream journal.

In thinking about them, you feel like you’re straddling the border between sanity and insanity. That’s an awful place to be.

Oftentimes, however, after you complete your analysis, the dream actually turns out to be mundane with an obvious meaning.

Are you insane? Insane people don’t know they’re insane. At the point when the conman was healing people (and remember the placebo effect is real) and conjuring materialized spirits, Kübler-Ross had lost objectivity. They’re not questioning their perceptions and assumptions. They’re adamant about them.

What’s going on is that you probably aren’t making sense yet of the symbols your subconscious is trying to communicate. Be patient. Those symbols will usually sort themselves out. Sometimes it just takes a little while.

A good way to tell if you’re going crazy

Try asking yourself two questions:

- Do I feel good about myself and where I am in life?

- Does my life feel out of control?

Those two issues are usually at the heart of anxiety-provoking dreams you don’t understand. Getting to the root of that, and understanding your answer to those questions can help.

Delusions, hallucinations, paranoia: they are the stuff of mental illness.

Mania, depression, suicidal thoughts: they are, too, right along with dementia and acute personality changes.

If the first answer is “no” and if the second is “yes” or if you’re unsure of your answer to these questions, it would be a good idea to see a mental health practitioner.

However, you should try to uncover the truth of your experiences whatever they are. Is it possible that your subconscious is using the image of the departed as a symbol, a way of communicating a message or a situation?

Ultimately, it’s up to you to decide the truth for yourself. Don’t be gullible. Don’t be naïve. Do your best to understand the science of how something works. Be objective to the greatest extent you can be.

The incidents at Shanti Nilaya stained Kübler-Ross’s otherwise stellar career. Discovering the Stages of Grief was world-changing. Much of what happened afterward was a tragedy.

Do you have any suggestions on how someone can decide whether they’re mentally imbalanced? Be sure to comment below.

Further reading:

Blast apart biases by thinking in bets

Compare yourself to others the right way

How to talk to others about your psychic experiences

Confront nightmares, fear, and hopelessness

Banner ads on the DRS contain affiliate links. If you click on a link and make a purchase, we receive a small portion. Our opinions remain independent.